Nearly 50,000 men lost their lives at Waterloo in 1815. The battle is typically remembered as the definitive defeat of Napoleon and the beginning of a century of comparative peace across Europe, yet the war had another lasting legacy: it gave lots of people new teeth.

This is the story of early dentistry and Waterloo Teeth.

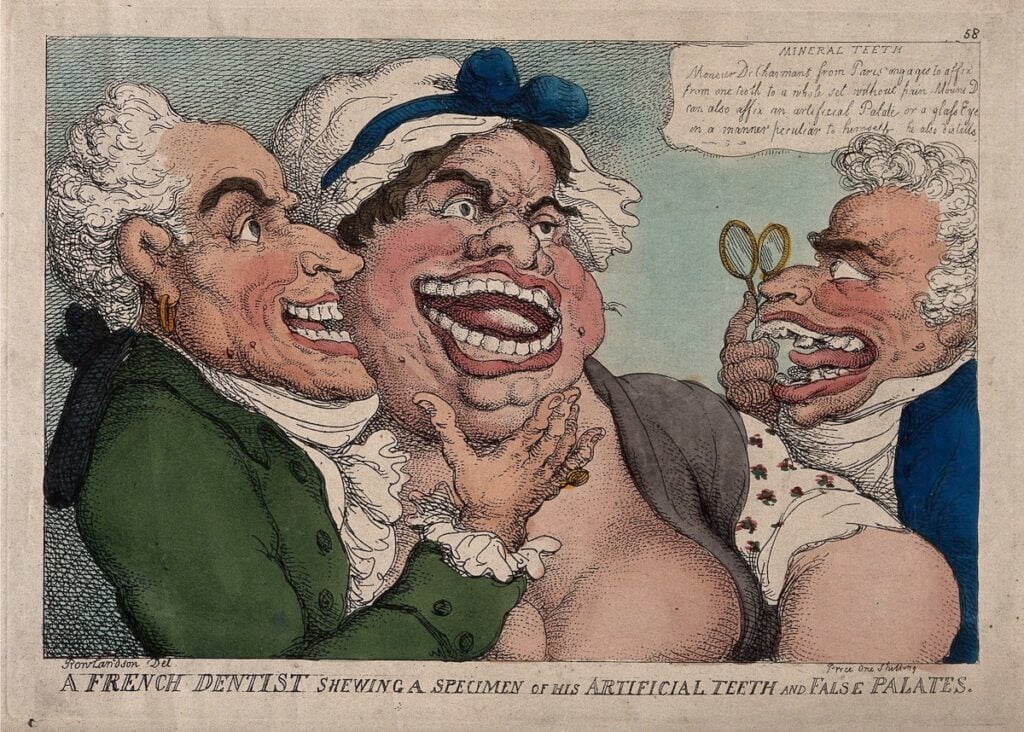

During the 18th and early 19th centuries, the concept of ‘dentistry’ as a full-time profession did not exist. Dental hygiene was, of course, considered, but it was driven by other industries and was by no means an established field of medicine. Instead, ivory merchants, jewelers, chemists, wigmakers and sometimes even blacksmiths led advancements in the field.

At the same time, the need for good dentistry was growing. Increased sugar consumption in the diets at the time, particularly among the wealthy, led to a growing need for teeth replacement. This was exacerbated by a growing trend for early attempts at teeth whitening – only they used acidic solutions which rapidly wore away tooth enamel.

By the 1780s in the United Kingdom, demand was so great that an ivory denture with human teeth could cost over £100. That’s almost £20,000 (over $25,000) in today’s money.

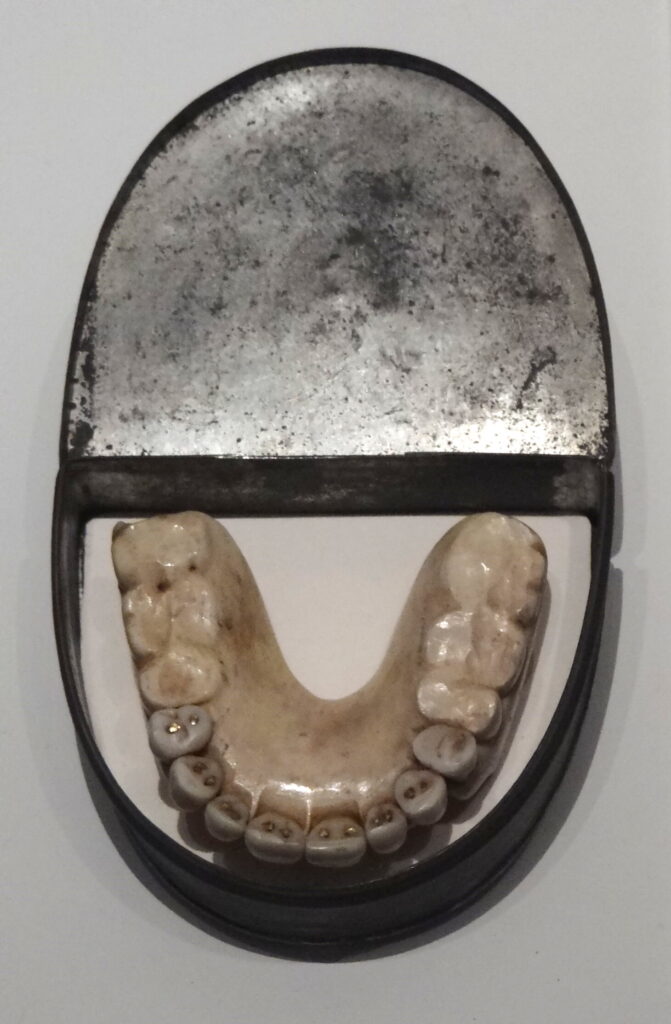

Early dentures were made out of a base plate of ivory, with animal teeth or teeth from young, healthy(ish) dead bodies. Sometimes, even the replacement teeth themselves were carved out of ivory. Demand also sadly led to some of the poorer people within society going so far as to sell their own teeth, effectively becoming living donors to the wealthy.

Then there were the resurrectionists – or body snatchers. They would dig bodies up from graves at best, selling fresh corpses to medical schools and focusing on the teeth of decaying ones. Murder was not off the cards, either, especially of beggars, drifters and prostitutes. History, it turns out, was a rather unpleasant place.

Forgive me for the morbidness of the next sentence, but based on all this you can see a tremendous potential wealth in a giant battlefield of recently dead young soldiers in the middle of Europe. British, French and Prussian soldiers died by the thousands and the looters were quick to arrive at Waterloo, located in modern-day Belgium.

Most of the opportunists were a combination of surviving soldiers, locals and scavengers who had traveled from Britain. Teeth were pulled out with pliers and then sold in as complete sets as possible. In cases where they were mismatched, early, unofficial dental technicians would boil and shape them.

By the 1840s, a breakthrough in American dentistry had led to vulcanite replacing ivory as the base of modern dentures. Charles and Nelson Goodyear were behind the breakthrough, made from natural rubber, which was both cheap and gum-colored.

Though the exact amount of teeth traced to the Battle of Waterloo is impossible to place, it’s believed there were enough that they were still being used into the mid-19th century. When the American Civil War began in 1865, the teeth from dead soldiers in the Union and Confederate armies furnished more modern dentures on both sides of the Atlantic.

Read More: Ulysses S. Grant and how his mammoth world tour changed America

Teeth were not the only reusable goods taken from the battlefields at Waterloo. In 2014, the late English journalist Robert Fisk wrote: “We didn’t always worship the corpses. After Waterloo, the bones of the dead – Wellington’s Britons and Napoleon’s French and Blücher’s Prussians – were freighted back to Hull to use as fertilizer for England’s green and pleasant land, military mulch from the 1815 battlefields which also yielded fresh teeth to be reused as dentures for the living. Hence my old Great War soldier Dad used to refer to “Waterloo teeth”. Tears for the departed, but no sentiment for the dead.”

With the two World Wars of the 20th century, the way we treat the dead most certainly changed.

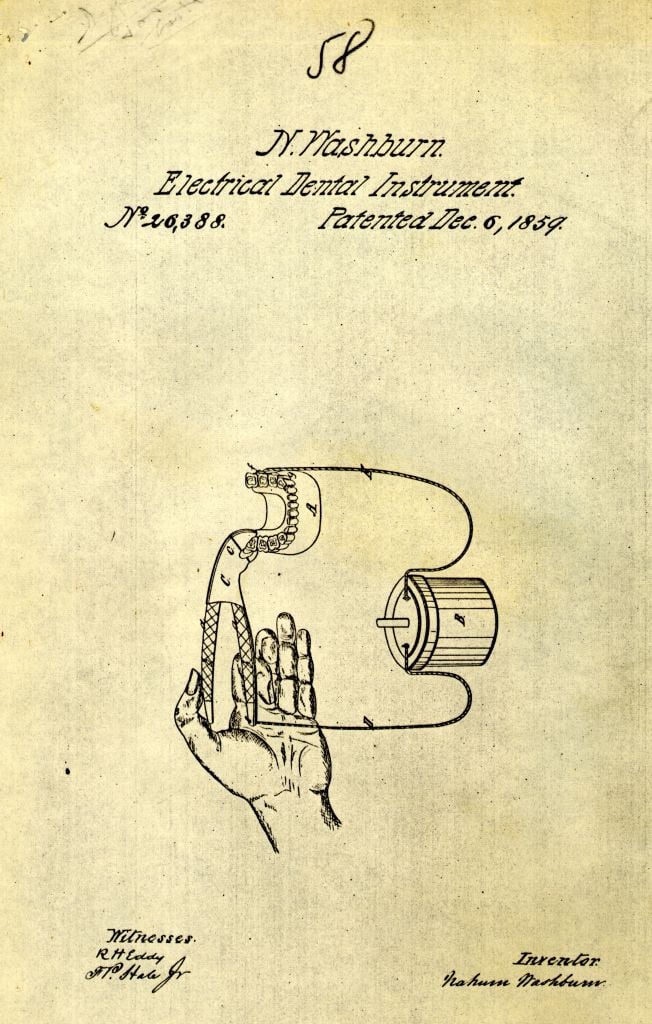

In terms of modern dentistry, it was not until 1860 that the UK introduced its first modern dental qualification – a Licence in Dental Surgery (LDS) at the Royal College of Surgeons of England, with royal surgical colleges in Edinburgh, Glasgow and Dublin, Ireland following suit.

In 1878, the UK passed its first dental legislation, and a year later the first register of dentists was created.

You don’t need us to tell you how far dentistry has come, but if you want to learn more, check out this video on how modern dental manakins are made: