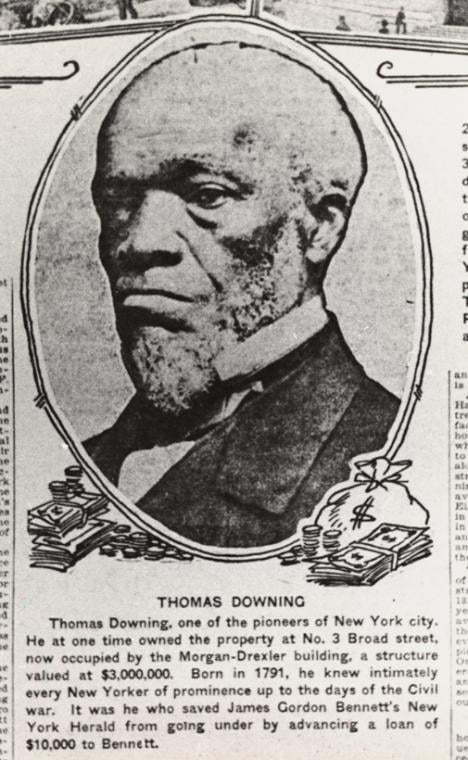

This is the unlikely and remarkable story of Thomas Downing. Born to formerly enslaved parents in Virginia in 1791, he went on to become a pioneering businessman at the heart of New York City’s rapid expansion. He was particularly noted for his oysters, supposedly the best in the city, served in an exclusive downtown Oyster house open to white customers only. He became the city’s “Oyster King”.

But little did people know that the money going into Downing’s pocket was funding an abolitionist movement, or that the exclusive Manhattan restaurant was, in actual fact, being used as a safehouse for escaped slaves moving northward on The Underground Railroad.

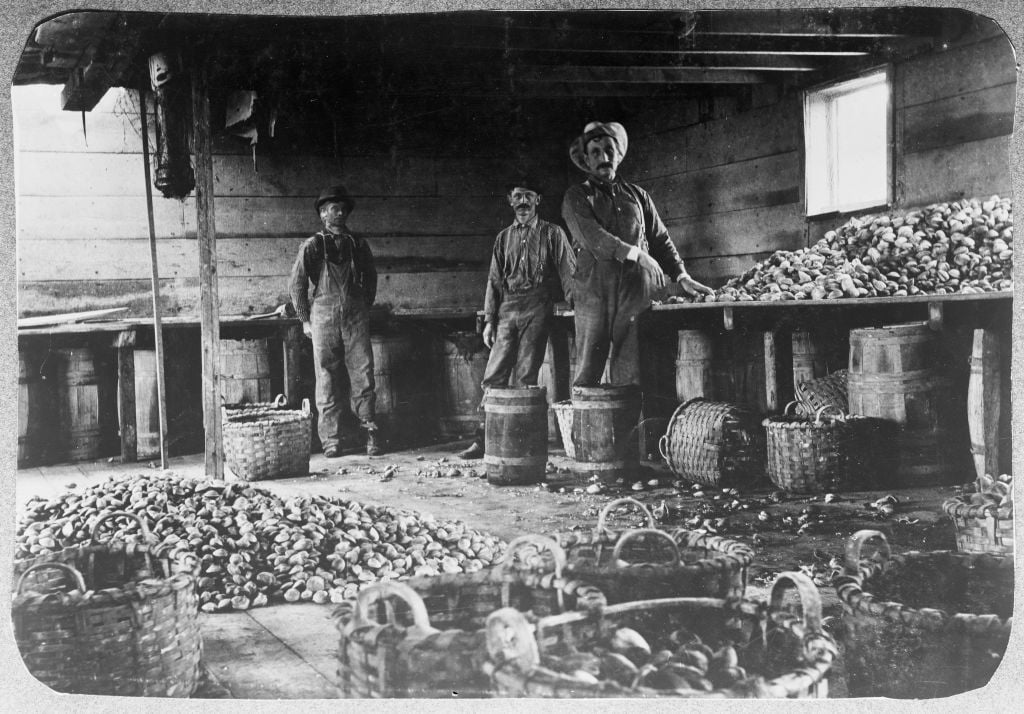

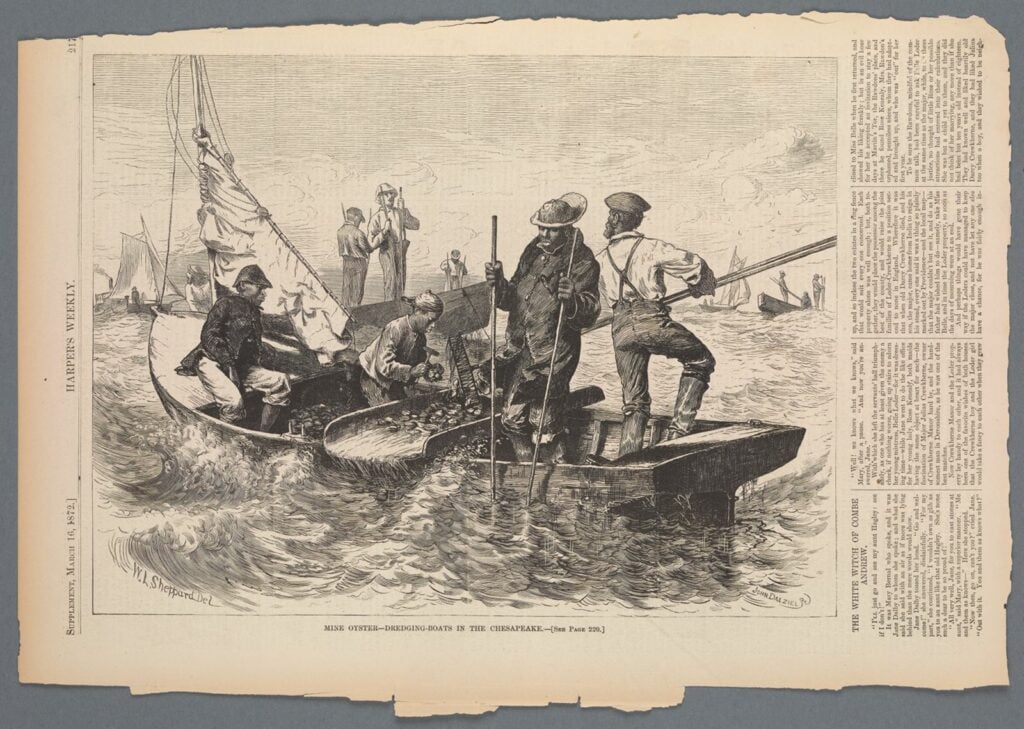

Downing’s native Chesapeake Bay, particularly Chincoteague Island, was famous for its Oyster industry. Though slavery was still legal in the state of Virginia, Thomas Downing was born free. His family made their living from fishing, with Downing picking up many of the professional attributes that would facilitate his success in later life.

He first left home after the War of 1812, joining the army and heading north to Philadelphia. Here he found work as a valet, as well as still oyster fishing, and he also met his first wife, Rebecca West. Together they had five children, including George, who would follow in his father’s footsteps becoming a prominent restauranteur, abolitionist and civil rights activist, as well as a close associate of Frederick Douglass. While in Philadelphia, Downing Sr opened his first Oyster House, but after having heard of the growing industry in New York and wanting to provide for his growing family, the Downings moved to the Big Apple.

1819 is the first year where Thomas Downing appears on the New York census, listed as an oysterman. He had a small skiff that he sailed across the Hudson Bay to the New Jersey flats, which was particularly flush with oysters.

Back in the 1820s, oysters were considered regularly common food. Most were sold on the street or in dark basements. They were not fine-dining, and far removed from the haughty reputation they hold now. Downing saw the opportunity, imagining a restaurant that combined the growing popularity of oysters with the growing wealth in New York, serving them in a respectable setting.

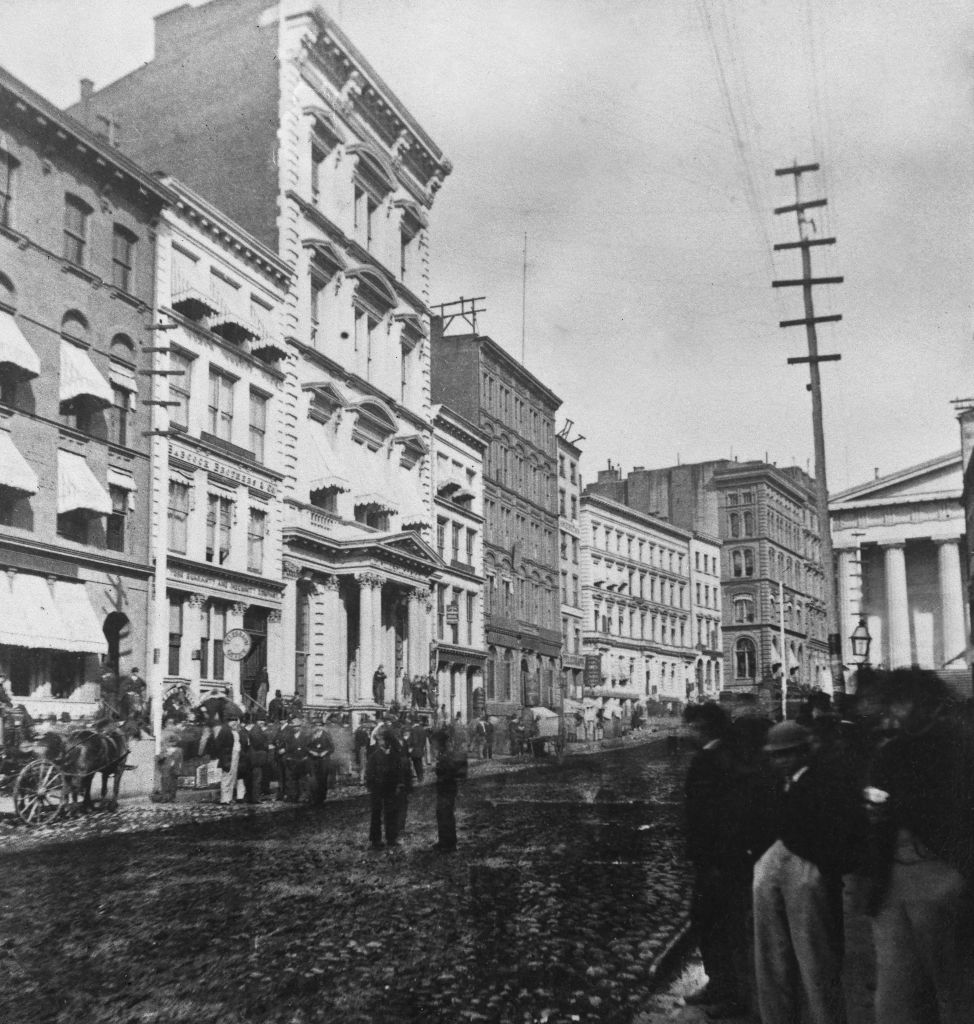

His location at 5 Broad Street, in downtown Manhattan, was integral to the success. It was around the corner from the banks on Wall Street. Also key was how good Downing’s eye for an oyster was. He was renowned for serving only the biggest, juiciest oysters that commanded a higher reputation, dining experience and, crucially, price.

Read More: How Jacksonville’s Norman Studios pioneered African-American representation on screen

In the following decades, the oyster house became a New York hotspot. The building on Broad Street was valued at $3,000,000, even in the 19th century. With chandeliers and mirrored hallways, it was a luxury restaurant and Downing’s status in the city grew to the extent that in 1842, he was chosen to cater the illustrious, multi-million dollar Boz Ball. An embodiment of high society, in that year it was also used to welcome Charles Dickens to America. Over 3,000 attended. Downing brought together some 50,000 oysters, 40 hams, 76 tongues, 50 rounds of beef, 50 jellied turkeys, 25 ducks, 2,000 mutton chops and more. The event is said to have passed without issue and Downing’s stock rose further.

It rather juxtaposes the other side of Downing’s life: fighting against racism and slavery as an abolitionist and civil rights activist. He used his money to co-found a group called the Committee of Thirteen, which worked to protect free black people from being kidnapped and taken back to the South to be enslaved.

Also staggering was how the building at 5 Broad Street, in the height of elite America, came to be used for shelter and safety by the escaped slaves on the Underground Railroad. It’s unknown how many people Downing, his family and his connections in New York, took in, but potentially as many as 100,000 people escaped the US along the famous route during the first half of the 19th century.

For all his wealth and status in the city at the time, Downing himself was the subject of at least one racial attack during his time in New York, according to Joanne Hyppolite, culture curator at the National Museum of African American History and Culture.

“He was on several trolley cars that were segregated and refused to leave his seat, just like Rosa Parks,” Hyppolite said. When Downing refused to move seats, others on the trolley ganged up to beat him. Hyppolite first learned about Downing when she was researching for an exhibition called Cultural Expressions. Last year, at the museum’s Sweet Home Cafe, they also recreated offerings that were once served at Downing’s New York City oyster house.

On April 10, 1866, just one day after gaining American citizenship in the Civil Rights Act of 1866, Thomas Downing died. Into his 70s, he’d become one of New York’s pre-eminent restauranteurs and businessmen. It’s reported that for the first time, due to demand from merchants, the New York Chamber of Commerce closed for the day of Downing’s funeral so that people could attend.

His son George was, by this stage, very involved with the restaurant and the abolitionist movement it was involved in. He ran the oyster house for another five years, until he moved to Washington D.C, becoming involved in national politics until his death in 1913.