In a brilliant series that we’re delighted to be able to bring to Great Big Story, British lexicographer Susie Dent will break down the stories behind ten different words every two weeks.

What better place to start than with some Americanisms…or are they?

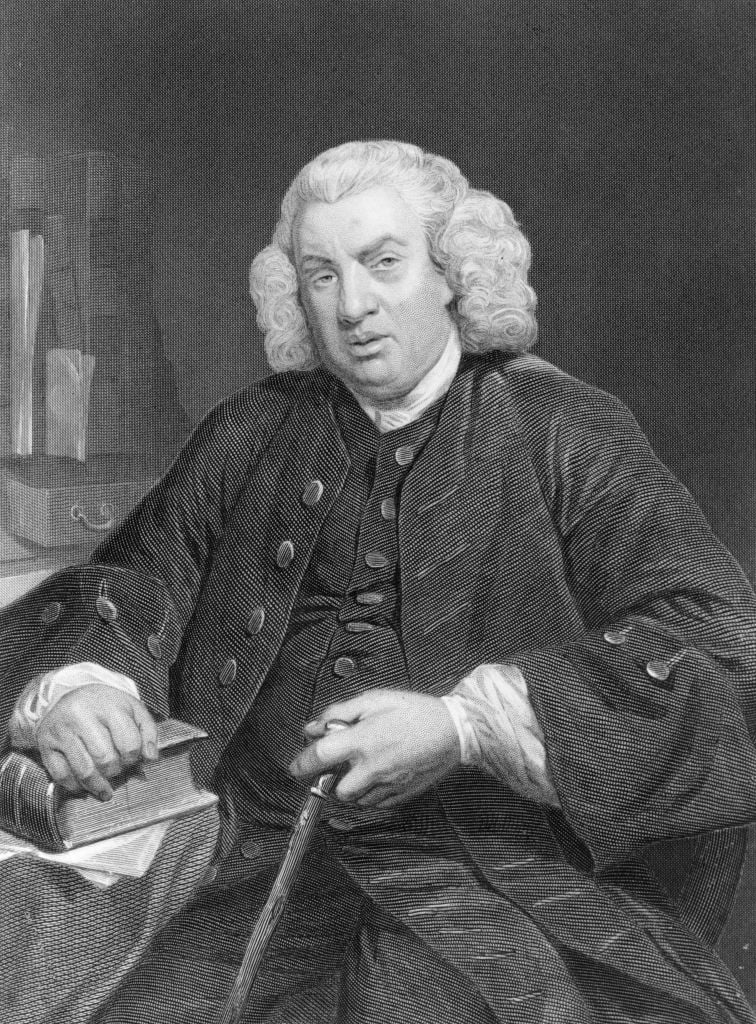

“I am willing to love all mankind, except an American”. Samuel Johnson didn’t hold much truck with his transatlantic neighbours, championing the need for a clear divide between the language of each nation. Judging by the furore that erupts every time Wordle sets an Americanism as its target, some of Johnson’s sentiment still lingers. American English is just so…unsophisticated and obvious, right?

Well, wrong, at least in my eyes. Where would we be without such glorious vocabulary as ‘skedaddle’, ‘finagle’, and ‘high-falutin’? Add this to the fact that a large proportion of the vocabulary we blame on North Americans was actually ours to begin with, and the complexion of things begins to change. Below are ten words we like to dismiss as pesky Americanisms, when their story is actually rather different.

1. Gotten

Many people loathe this past tense of ‘got’, dismissing it as a slangy Americanism that clutters any sentence. In fact, ‘gotten’ dates back as far as Middle English, and is preserved in such expressions as ‘ill-gotten gains’. US English rather likes a ‘strong’ verb – one that changes its stem in the past tense, producing such beauties as ‘I dove into the pool’. British English, on the other hand, favours chucking a (rather lazy) ‘-ed’ at the end of everything.

2. Fall

A perfectly serviceable term for the leafy season in 16th-century British English, alongside ‘harvest’, until it was ousted by ‘autumn’ thanks to the fashionability of French. It is simply a rather poetic shortening of the ‘fall of the leaf’, just as ‘spring’ is short for ‘spring of the leaf’.

3. Honor

How we look down upon American spelling. And yet if you were to search the First Folio of William Shakespeare’s plays, you’ll find that ‘honor’ is found over 100 times more than ‘honour’. Similarly, ‘humor’ outscores ‘humour’, and ‘center’ pips ‘centre’ with ease.

4. Aluminum

British English was very happy with calling the silvery-grey metal ‘aluminum’ for a while, as it neatly matched up with ‘platinum’. At some point it was decided that ‘magnesium’ was a better model, and so we plumped for ‘aluminium’ instead.

5. Transportation

One of the most major beefs about US English is how it extends everything unnecessarily. Such as ‘transportation’, which was actually first recorded in British English in the 17th century, until it was slowly given up for ‘transport’ to avoid any association with penal transportation. In the same way, we were merrily ‘obligating’ people to do things in the 16th century – a verb that is actually closer to its roots in the Latin obligare than ‘oblige’.

6. Trash

First recorded in British English in 1555 to mean random bits of wood, ‘trash’ is also defined in the English Dialect Dictionary as ‘cuttings from a hedge’. By extension, on both sides of the Atlantic, it was eventually applied to any dregs or refuge.

Read More: Hot Lips | How the Rolling Stones found their logo

7. Wow

Far from being the sort of over-the-top exclamation we associate with US English, this is first recorded in a 16th-century translation of Virgil’s epic poem Aeneid. Wow!

8. Realize

For some inexplicable reason British (or Twitter’s) hackles are never so raised as when someone uses the American -ize in verbs such as ‘realize’. In fact, this is the house style of Oxford Dictionaries, not least because the z is closer to the Greek origin of such verbs. It seems the Americans even know a thing about etymology.

9. Sidewalk

In 1605, the Charters & Documents Burgh of Paisley speaks of a minor path or walkway as a ‘sidewalk’, with no sign of the curl of the lip or sigh that might accompany its use in Britain these days.

10. Oftentimes

Frequently labelled as an Americanism no one wants on British shores, this adverb was adorning sentences as early as the 14th century, joining other lost markers of time that have sadly disappeared from our English. Surely it’s high time we borrowed it back.