This summer, China began digging a hole in the Xinjiang region with an eventual depth of over 36,000ft. This will mean cutting through 10 layers of continental strata and reaching rocks as old as 145 million years. Yet even when they get there, expected to be in late 2024, this won’t be the deepest hole that humans ever dug.

Nope, that title will still belong to the Kola Superdeep Borehole in north-west Russia, which stretches over 40,000ft (7.5 miles) down and is the result, at least in part, of Cold War competition.

This is the story of the deepest hole in the world.

Ever wondered how far down you could dig at the beach? It’s not a great idea – sand is famously unstable and holes can cave in – but there’s something rather natural about trying to see just how far underground you could go.

In the mid-to-late 20th century, both the United States and the Soviet Union thought the same thing. Though the Cold War rivalry was more famously embodied by the ‘Space Race’, both nations embarked on ambitious projects to explore down the way, as well as up.

Drilling on the Kola Superdeep Borehole began back in May 1970, as part of a ‘scientific project’ by the Soviet Union. By 1979, the project had burrowed down over 31,000ft, surpassing the previous record of Bertha Rogers hole – an exploratory oil project in Oklahoma.

It was not America’s only project at that time. While the Soviets opted for the Arctic Circle, the Americans chose a rather different location for their flagship hole.

Known as ‘Project Mohole’, after the boundary between the earth’s crust and mantle, it began during the late 1950s and was overseen by the ‘American Miscellaneous Society’ At the time, it was the first serious plan to drill down to earth’s mantle. The group decided that instead of drilling from land, they would cut through the floor of the Pacific Ocean, picking a site near Guadalupe, in Mexico.

READ: Inside London’s Super Sewer | The mammoth new tunnel under the River Thames

While we now have advanced technology for deep-sea drilling, it was not nearly as developed when the team on Project Mohole started drilling in the early 1960s. Propellors were used to try and keep the drilling vessel in place, and they were successful in dislodging a few meters of basalt – the volcanic rock caused by rapid cooling of lava near the earth’s surface – but the project was canceled in 1967, US Congress shutting it down with costs spiraling.

John Steinbeck, the American author, covered the project at the time. Soon after it was shut down, he wrote: “Project Mohole has barely started and I hope I may be invited back when the new ship sails towards new wonders in about two years.” That time never came.

At first, the Soviets were not plagued by the same financial issues. It took them 20 years, but the Kola Superdeep Borehole not only got lower than anybody had before, but made a series of groundbreaking discoveries that shaped our understanding of the inner workings of the planet. For one, the temperatures were much higher than they expected; water, too, was found far deeper into the earth’s surface than scientists believed at the time. The most groundbreaking discovery of all, however, was fossils. At 22,000ft down, they discovered 24 species of microfossils that were 2 billion years old, and the rocks at the very bottom of their eventual hole were 2.7 billion years old, known as Precambrian (Archean) granites.

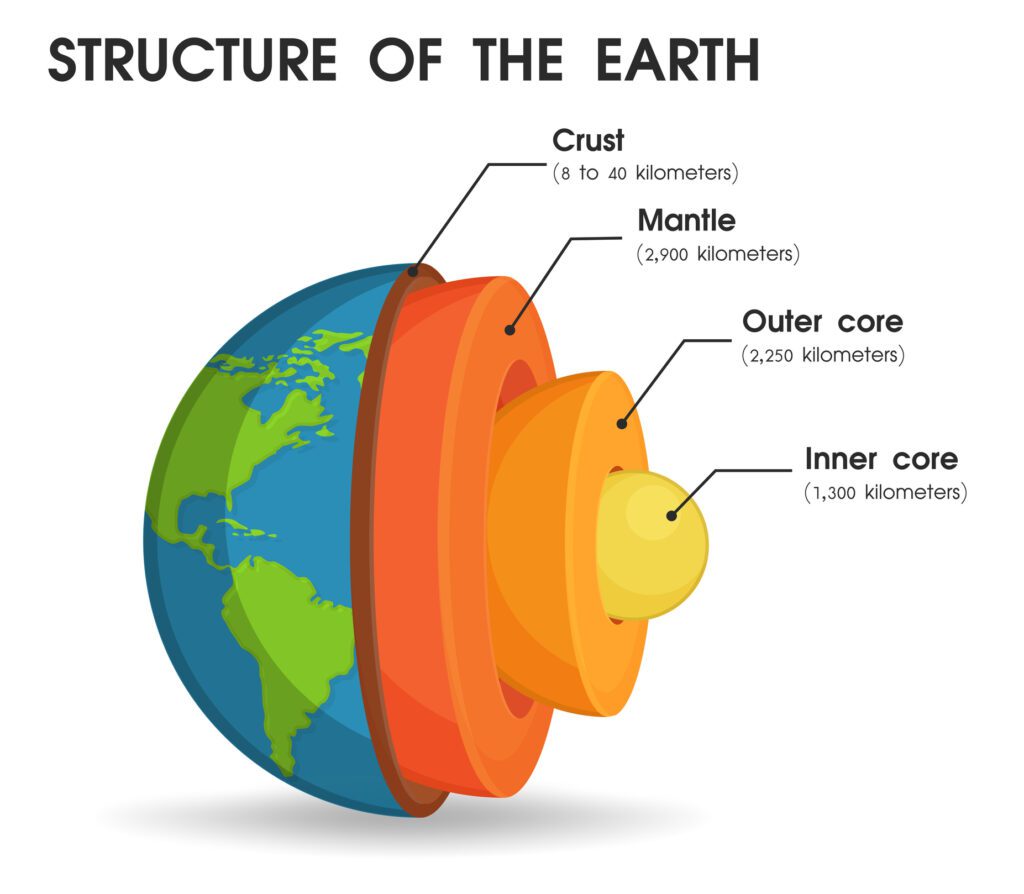

Despite the success, the discoveries the Soviets made also contributed to their inability to go any further. The density of the rocks made it far harder to drill, and temperatures meant the drilling technology was unable to function facing heat of around 356 degrees Fahrenheit (180 degrees Celsius). It means the hole still (quite literally) only scratches the earth’s surface. It penetrated a third of the way through the crust, the layer of the world we stand on, which is about 25 miles thick. The mantle, for perspective, is 1800 miles thick. The outer and inner cores are over 2,000 miles thick combined.

In total, the Kola Superdeep Borehole made it only 0.2% of the way to the world’s center.

Rumour has it that the Soviet project stopped because they breached the gates of hell. Local folklore said that they breached a chamber and heard the tortured screams of those confined to the underworld for eternity. It is far more likely that drilling stopped in 1992 because of a lack of funding after the fall of the Soviet Union.

The site is now abandoned. An innocuous manhole, the kind you might walk past without blinking twice, covers the hole. You’d have no idea, with a diameter of just nine inches, that this is the world’s deepest manmade hole, stretching deeper even than the Mariana Trench – the deepest part of the oceans.

Though the American Project Mohole was less successful at the time, it proved instrumental in the exploration of the deep sea, and got another key component right: it’s much easier to reach the earth’s mantle from the sea than it is from land. This is why the Japanese Agency for Marine-Earth Science and Technology is taking on a project called M2M – ‘Mohole to Mantle’. Instead of the 25-mile crust that exists under land, it’s only about 3.7 miles thick under certain parts of the seabed.

Three drilling sites have been discussed as candidates. One is off Costa Rica, one is off Baja, California, and the final one is north of Hawaii. A huge drilling ship known as Chikyū was built with the project in mind, equipped with a GPS system and “six adjustable computer-controlled jets that can alter the position of the huge ship by as little as 20in,” the BBC reports.

“The idea is that this ship would pick up the torch and continue the work started by the original Mohole project 50 years ago,” Sean Toczko, program manager for the Japan Agency for Marine-Earth Science, said. “Superdeep boreholes have made a lot of progress in telling us about the thick continental crust.”

The aim of the $1bn drilling project is to recover the “in-situ” mantle rocks for the first time in human history.